Quick summary:

- Many “mystery” flavors in the cup are not origin issues but roast defects such as underdevelopment, baking, scorching, tipping or overdevelopment.

- Each defect has a characteristic sensory profile in the cup and often stems from common factors in the roast profile, batch load, or heat transfer.

- You can train yourself to recognize these patterns and make targeted adjustments, such as modifying the charge temperature, batch size, heat application, airflow, or development time, to minimize defects.

- A more stable and even heat transfer across the bean mass makes it easier to avoid overheating related defects. Systems that rely on controlled convection and minimise direct metal contact can help reduce the risk of scorching and similar issues.

Why roast defects matter for your roastery

You can source excellent green coffee, design attractive packaging, and perfect your brew recipes, but if your roast contains defects, much of that value is lost in the cup.

Roast defects have three key impacts:

- They mask the positive characteristics of the coffee.

- They make flavor inconsistent from batch to batch.

- They can gradually harm your brand, as regular customers notice inconsistency before anyone else does.

The good news is that most common roast defects can be identified in the cup with practice. Once you can recognize what you are tasting, you can adjust the roast profile to address the root cause rather than relying on guesswork.

This guide focuses on five common roast defects that are most likely to occur in a startup roastery and how to address them.

The defects covered include:

- Underdeveloped coffee

- Baked coffee

- Overdeveloped coffee

- Scorched beans

- Tipping

How to taste for roast defects

You do not need a specialized lab to identify roast defects.

- Cup your production roasts regularly.

- Always include a trusted reference coffee as a benchmark.

- Taste the same coffee at different temperatures, from hot to cool, as many defects become easier to detect as the coffee cools.

When a coffee tastes “off,” use the patterns below as a guide rather than a strict diagnosis. Real-world roasts can exhibit multiple defects simultaneously.

1. Underdeveloped coffee

How it tastes

Underdeveloped coffee often tastes like:

- Raw, green, grassy notes

- Hay, fresh peas, sometimes raw starch

- High, sharp acidity with minimal sweetness or body

You can sense that the bean had potential, but the sweetness and complexity never fully developed.

What is happening in the roast

Chemically, the roast was stopped before the sugars and internal structure had sufficient time and temperature to fully develop. Research describes underdeveloped roasts as those in which the bean temperature and the time to first crack are too low to achieve proper caramelization and Maillard reactions.

Typical causes:

- Too low energy application in the early and middle stages.

- Ending the roast too soon after first crack.

- Very small batch size in a roaster that is tuned for heavier loads.

What you can try

- Increase energy earlier in the roast so you reach first crack on time without stalling.

- Extend development time slightly after first crack, while keeping an eye on end temperature.

- If you are roasting tiny batches, increase the charge weight or adjust your gas and airflow to suit smaller loads.

The goal is not “always roast darker”. The goal is to give the bean enough internal development at your chosen roast level.

2. Baked coffee

How it tastes

Baked coffee is one of the most frustrating defects because it hides inside the profile:

- Flat, dull, “empty” cup

- Low sweetness and acidity

- Flavours that remind you of bread crust, oats or paper

Nothing is aggressively wrong. It is just boring.

What is happening in the roast

Baked coffee usually occurs when beans remain in the roaster too long at moderate heat without sufficient energy to drive the roast forward. The temperature curve tends to “stall” just before or shortly after first crack.

Common causes:

- Rate of rise collapses in the middle phase.

- Trying to stretch the roast to “smooth acidity” without enough heat.

- Very long total roast time at medium temperature.

What you can try

- Ensure the rate of rise does not collapse before first crack. It should decline gently, not drop sharply.

- Shorten total roast time by applying more energy earlier and reducing heat slightly sooner, rather than extending the roast at low temperatures.

- Verify that your machine can provide sufficient heat for the batch size you are using.

Consider baking as a loss of momentum. Your goal is to maintain forward progress in the roast without rushing to the finish.

3. Overdeveloped coffee

How it tastes

Overdeveloped coffee is on the other side of the spectrum:

- Very low acidity

- Dominant bitter, smoky, sometimes “charcoal” notes

- Generic dark roast flavour where origin character disappears

The beans often look very dark and oily in the bag.

What is happening in the roast

Overdeveloped coffee occurs when the roast continues for too long or reaches an excessively high end temperature. Structural sugars and delicate aromatics break down into simpler, bitter compounds. Research describes overdeveloped roasts as having flavor profiles dominated by burnt and smoky notes.

Typical causes:

- Long development after first crack.

- Very high end temperature.

- Chasing “body” or “chocolate notes” by simply pushing the roast deeper.

What you can try

- Shorten development time and lower the target drop temperature.

- Monitor color changes in the trier and on the bean surface.

- Taste side by side: current profile versus a batch dropped 30–60 seconds earlier.

Some customers love darker roasts, but overdevelopment is when “dark” becomes “burnt” and origin character is gone.

4. Scorching

How it tastes

Scorched beans give a very specific combination:

- Smoky, ashy, burnt flavours

- Bitter aftertaste

- Sometimes a strange mix of burnt and still slightly green notes

On the bean, you will often see dark patches or “burn marks” on the flat side of the seed.

What is happening in the roast

Scorching happens when parts of the bean surface receive too much direct heat. Typical scenarios described in technical guides:

- The charge temperature is too high, causing beans to be shocked by the metal surfaces.

- Drum speed or airflow is insufficient, so beans are pressed against hot metal instead of moving freely.

- The batch is overloaded, which reduces movement and airflow through the coffee mass.

What you can try

- Lower the charge temperature or apply heat more gradually at the start.

- Increase drum speed or airflow to ensure beans move freely from the first seconds.

- Reduce batch size if movement appears sluggish.

The goal is to keep beans in motion and surrounded by evenly heated air, rather than pressed against a single hot spot.

5. Tipping

How it tastes

Tipping is a close cousin of scorching:

- Bitter, ashy, slightly burnt flavours, often more subtle than full scorching

- Sometimes sharp, unpleasant notes that show more as the cup cools

Tipping appears visually as small burn marks on the tips or edges of the bean, rather than on the flat surface.

What is happening in the roast

Tipping often occurs when:

- Heat application is too aggressive during the later stages, particularly around second crack.

- Beans are forced against surfaces due to a combination of high heat and limited movement.

- The charge temperature is too high for the density and screen size of the coffee.

What you can try

- Soften heat application as you approach first and second crack, rather than increasing it.

- Adjust the profile for denser or larger beans with a slightly lower charge temperature and more gradual energy input.

- Ensure beans are not stuck against surfaces due to low drum speed or overloaded batches.

If scorching appears as large burns, tipping shows as many small ones. The solution is the same: reduce shock and provide more even heat.

A quick “defect map” for your cupping table

When cupping, if something tastes off, it may be caused by:

- Grassy, raw, sharp acidity, no sweetness

→ likely underdeveloped, try more energy earlier and longer development. - Flat, dull, “oatmeal” or cardboard, no sparkle

→ likely baked, check for stalled rate of rise and overly long roast times. - Very dark, bitter, smoky, no origin character

→ likely overdeveloped, shorten development and lower drop temperature. - Bitter, ashy, smoky with visible burn patches on bean surface

→ likely scorching, reduce charge temperature, improve movement and airflow. - Bitter, ashy with small burns on edges or tips

→ likely tipping, soften later heat application and adjust for bean density.

This map is not perfect, but it gives you a starting point for turning “something is wrong” into “this is probably baked, let’s fix the middle phase”.

A note on heat transfer and how equipment can help

All of these defects share a common cause: uneven or poorly controlled heat transfer.

When some parts of the bean mass overheat while others lag behind, it results in a mix of underdevelopment, baking, and surface burns. Technical literature and manufacturer case studies indicate that roasting technologies emphasizing controlled convection and minimizing direct metal contact can help reduce risks such as scorching, tipping, and baking by distributing heat more evenly throughout the coffee mass.

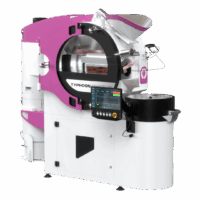

This is one reason why many modern roasteries choose air-driven, fluid-bed roasters, such as Typhoon, when aiming for cleaner and more consistent flavor profiles. While these roasters do not replace the expertise of a skilled roasting master, they allow you to focus on developing flavor rather than managing hot spots and burnt patches.